What data recovery tools to buy if you want to start a data recovery business?

Free video data recovery training on how to recover lost data from different hard drives?

Where to buy head and platter replacement tools at good prices?

Data recover case studies step by step guide

I want to attend professional data recovery training courses

FAT Boot Sector

Because the MBR transfers CPU execution to the boot sector, the first few bytes of the FAT boot sector must be valid executable instructions for an 80×86 CPU. In practice these first instructions constitute a “jump” instruction and occupy the first 3 bytes of the boot sector. This jump serves to skip over the next several bytes which are not “executable.”

Following the jump instruction is an 8 byte “OEM ID”. This is typically a string of characters that identifies the operating system that formatted the volume.

Following the OEM ID is a structure known as the BIOS Parameter Block, or “BPB.” Taken as a whole, the BPB provides enough information for the executable portion of the boot sector to be able to locate the NTLDR file. Because the BPB always starts at the same offset, standard parameters are always in a known location. Because the first instruction in the boot sector is a jump, the BPB can be extended in the future, provided new information is appended to the end. In such a case, the jump instruction would only need a minor adjustment. Also, the actual executable code can be fairly generic. All the variability associated with running on disks of different sizes and geometries is encapsulated in the BPB.

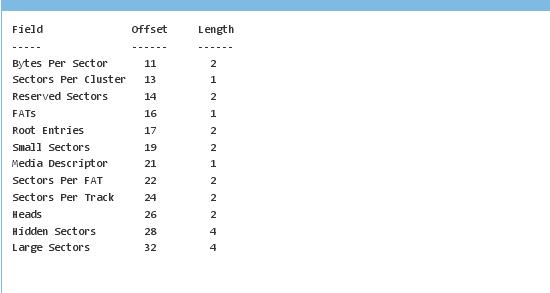

The BPB is stored in a packed (that is, unaligned) format. The following table lists the byte offset of each field in the BPB. A description of each field follows the table.

Bytes Per Sector: This is the size of a hardware sector and for most disks in use in the United States, the value of this field will be 512.

Sectors Per Cluster: Because FAT is limited in the number of clusters (or “allocation units”) that it can track, large volumes are supported by increasing the number of sectors per cluster. The cluster factor for a FAT volume is entirely dependent on the size of the volume. Valid values for this field are 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, and 128. Query in the Microsoft Knowledge Base for the term “Default Cluster Size” for more information on this subject.

Reserved Sectors: This represents the number of sectors preceding the start of the first FAT, including the boot sector itself. It should always have a value of at least 1.

FATs: This is the number of copies of the FAT table stored on the disk. Typically, the value of this field is 2.

Root Entries: This is the total number of file name entries that can be stored in the root directory of the volume. On a typical hard drive, the value of this field is 512. Note, however, that one entry is always used as a Volume Label, and that files with long file names will use up multiple entries per file. This means the largest number of files in the root directory is typically 511, but that you will run out of entries before that if long file names are used.

Small Sectors: This field is used to store the number of sectors on the disk if the size of the volume is small enough. For larger volumes, this field has a value of 0, and we refer instead to the “Large Sectors” value which comes later.

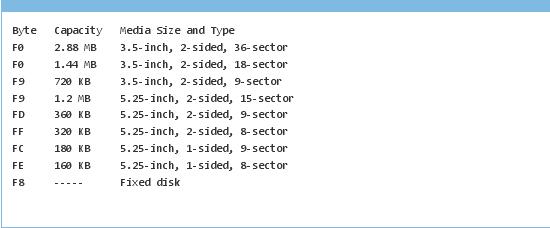

Media Descriptor: This byte provides information about the media being used. The following table lists some of the recognized media descriptor values and their associated media. Note that the media descriptor byte may be associated with more than one disk capacity.

Sectors Per FAT: This is the number of sectors occupied by each of the FATs on the volume. Given this information, together with the number of FATs and reserved sectors listed above, we can compute where the root directory begins. Given the number of entries in the root directory, we can also compute where the user data area of the disk begins.

Sectors Per Track and Heads: These values are a part of the apparent disk geometry in use when the disk was formatted.

Hidden Sectors: This is the number of sectors on the physical disk preceding the start of the volume. (that is, before the boot sector itself) It is used during the boot sequence in order to calculate the absolute offset to the root directory and data areas.

Large Sectors: If the Small Sectors field is zero, this field contains the total number of sectors used by the FAT volume.

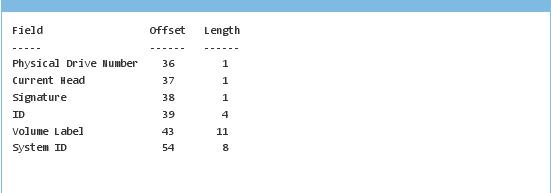

Some additional fields follow the standard BIOS Parameter Block and constitute an “extended BIOS Parameter Block.” The next fields are:

Physical Drive Number: This is related to the BIOS physical drive number. Floppy drives are numbered starting with 0x00 for the A: drive, while physical hard disks are numbered starting with 0x80. Typically, you would set this value prior to issuing an INT 13 BIOS call in order to specify the device to access. The on-disk value stored in this field is typically 0x00 for floppies and 0x80 for hard disks, regardless of how many physical disk drives exist, because the value is only relevant if the device is a boot device.

Current Head: This is another field typically used when doing INT13 BIOS calls. The value would originally have been used to store the track on which the boot record was located, but the value stored on disk is not currently used as such. Therefore, Windows NT uses this field to store two flags:

* The low order bit is a “dirty” flag, used to indicate that autochk should run chkdsk against the volume at boot time.

* The second lowest bit is a flag indicating that a surface scan should also be run.

Signature: The extended boot record signature must be either 0x28 or 0x29 in order to be recognized by Windows NT.

ID: The ID is a random serial number assigned at format time in order to aid in distinguishing one disk from another.

Volume Label: This field was used to store the volume label, but the volume label is now stored as a special file in the root directory.

System ID: This field is either “FAT12” or “FAT16,” depending on the format of the disk.

On a bootable volume, the area following the Extended BIOS Parameter Block is typically executable boot code. This code is responsible for performing whatever actions are necessary to continue the boot-strap process. On Windows NT systems, this boot code will identify the location of the NTLDR file, load it into memory, and transfer execution to that file. Even on a non-bootable floppy disk, there is executable code in this area. The code necessary to print the familiar message, “Non-system disk or disk error” is found on most standard, MS-DOS formatted floppy disks that were not formatted with the “system” option.

Finally, the last two bytes in any boot sector always have the hexidecimal values: 0x55 0xAA

Comments are closed

Sorry, but you cannot leave a comment for this post.